Trauma robs you of the feeling of being in charge of yourself. In order to regain control over yourself, trauma needs to be revisited. However, trauma is much more than a story about something that happened. The emotions and sensations imprinted during trauma are experienced not only as memories but as disruptive physical reactions in the present.

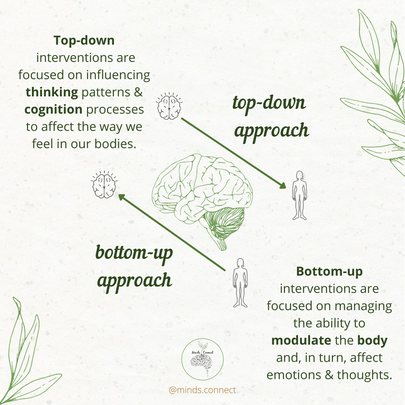

Once you learn to tolerate physical experiences based on trauma, you can begin to make sense of them, to integrate them into your life history and personal identity. Integrating trauma also means putting it in its place on a body level. Bessel van der Kolk, M.D., believes that contemporary mind-body interventions actually promote change by forging communication and restoring the balance between the rational and emotional brain systems through a third pathway: the medial prefrontal cortex.This area manages the emotion regulation/inhibition process and it is also connected to the amygdala, that is the threat detector of our brain. Mindfulness practices, for example, help to strengthen the medial prefrontal cortex increasing emotional regulation capacity. Neuroscience research shows that the only way we can change the way we feel is by becoming aware of our inner experience and learning to befriend what is going on inside ourselves. Traditional talk-based psychotherapy, and most cognitively-oriented trauma-focused therapies, are viewed as taking a top-down approach to treatment. Most often this involves efforts to resolve trauma symptoms by working with the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, the area of the brain most responsible for logic and reason. A top-down approach in psychotherapy starts with looking at how the mind is interpreting information, how do we make sense of events. It focuses first on the cognitive aspect and targets the frontal lobes. The higher brain is the place where logic lives. A logic-first approach can be less effective because, if your brain has experienced trauma, the trauma response de-activates the thinking areas, and activates the lower areas of the brain. Some of the top-down therapies are: - Talking therapies:

The bottom-up approach begins with information acquired from the body’s sensations. The bottom-up approach understands that feelings and body sensations happen first, before it access the rational areas of our brain. Therefore, bottom-up interventions work by accessing the limbic system (emotional brain) and by directly targeting sensory receptors located throughout the body. The idea is to develop a sense of safety within your own body. Trauma-informed therapy creates healing relationships in which it is safe to begin to look at the reasons why a person feels unsafe (and unable to control thoughts and feelings when triggered), without being overwhelmed by taking a tritration approach. Titration is the skill set that involves managing the speed of processing by slowing down the activation/ arousal responses. The healing relationships include the therapist-client relationship and the client’s own relationship with himself or herself. This is why it is so important that you feel safe and connected with your therapist. To activate this bottom-up process, the following activities could be used: - Exercise - Rhythmic movement - Deep, relaxed diaphragmatic breathing - Synchrony exercises between breathing and heart rate Some of the bottom-up therapies are: - Sensorimotor therapy - Somatic experiencing - Yoga therapy - Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) - Ego states psychotherapy / Internal Family Systems (IFS) - Mindfulness-based therapies - Neurofeedback While either path can help a client begin to self-regulate, it is important to think about what a specific person may need. A blend of both can help individuals to begin to cope with their bodily experiences of trauma while they begin to think and feel differently about their experiences, their emotions, and their sense of self. See more about this in my Instagram post. Please leave your comments below!

1 Comment

Despite its considerable public health importance, childhood attachment is very much under-represented in medical training and practice.

According to attachment theory, pioneered by British psychiatrist John Bowlby and American psychologist Mary Ainsworth, the quality of the bonding we experience during our first relationship (infant-caregiver) often determines how well we relate to other people and respond to intimacy throughout life. This will impact not only our adult interpersonal connections and how we feel about them, but also it will affect our capacity to regulate our emotions in situations of distress and danger. We are all born with attachment-seeking behaviours such as crying, clinging, imitation & smiling. These behaviours are designed to keep caregivers close, and to ensure that the baby’s needs for survival, sensitive care and safety are met. Attachment is a process. Attachment is an evolutionary adaptation, is not a diagnosis. Attachment allows children the ‘secure base’ necessary to explore, learn and relate. It is important for safety, emotional regulation, adaptability and resilience. Attachment with the caregiver allows emotional regulation to develop. Through co-regulation the caregiver soothes the child's emotional distress. Attuned parenting provides meaning to the ‘inner world’ of the child. Through verbal and non-verbal communication the caregiver reflects back to their child what they believe is happening in the child's mind that is the basis for emotional regulation. Through this process, the child learns to self-regulate. We cannot do everything alone. We are not capable of healing in isolation, we are interdependent since we are born. The presence of those close to us makes a difference even in the most horrible circumstances. Our culture might encourage us to think of ourself as do-it-yourself projects, but we get more positive results when we adopt a we-can-do-it-together approach. The type of attachment we have experience in our early years and childhood creates a template that serves as a predictor of the types of attachment adaptations we expect to form in adulthood. It will create a blueprint and it will be re-enacted in every relationship we have based on our perceived level of safety / threat. Secure attachment Secure attachment is attunement. This adaptation is marked by emotional availability, ability to express one's needs, self-sufficiency and healthy boundaries. Diane Poole Heller says in her book that she believes that we all long for love and connection and that such longing comes directly from our secure attachment system, which is inherent in everyone, no matter our attachment style. Secure attachment reflects a positive-enough environment that creates and engenders basic trust. Main ingredients for an upbringing environment that promotes secure attachment:

Avoidant attachment This adaptation is marked by fear off intimacy and closeness, relational discomfort and difficulties recognizing and expressing one's needs. Adults with the avoidant adaptation are sometimes denigrated as “Detached,” “off in their own world,” “insensitive,” “cold,” “standoffish,” “lone wolf,” “workaholic”. People with an avoidant adaptation tend to regularly experience approach stress, even with people they love. However, we know that avoidant people actually do want connection, they just need more transition from alone to together time to take the pressure off and ease the way for a smoother path to connection. Diane Poole in her book recommends that those who align with the avoidance adaptation try to focus a little more on physical embodiment and emotional presence. Main ingredients for an upbringing environment that may result in avoidant attachment adaptation:

Anxious attachment This adaptation is marked by fear of rejection, hypersensitivity to perceived threat, need for reassurance and for intense interaction with others. Adults with the anxious attachment adaptation are sometimes denigrated as “needy,” “clingy,” “oversensitive,” “controlling,” “high-maintenance,” or “high-strung.” Diane Poole explains in her book that people with an anxious attachment adaptation tend to feel upset when are alone and not in close proximity to the important people in their life. They might be high-functioning and in contact with their secure attachment network when in the presence of their relationship partner, but as soon as their loved one leaves, they begin to mistrust the connection. People with anxious adaptation may find more difficulty to transition from together to alone time. This may be explained by the fact that they rely on "external regulation", constantly looking to use others to down regulate, or calm, their overactivated nervous systems. These individuals may benefit from learning to feel safe alone and use self-regulation and grounding techniques. Main ingredients for an upbringing environment that may result in anxious attachment adaptation:

Disorganized attachment This adaptation is marked by emotional dysregulation, confused sense of self, internal conflict, feelings of constant overwhelm, controlling behaviours, ongoing sense of failure and lack of impulse control. In some ways, disorganized attachment is a combination of the avoidant and ambivalent adaptations, but it is mixed with fear-induced survival defenses switched on to deal with ever-looming threat. The disorganized adaptation comes with a lot of confusion — cognitive, emotional, and somatic. This creates lack of confidence and sense of ongoing failure. Disorganized people with these feelings often don’t like to try new things because they’re convinced they’re going to fail at whatever they do. People with disorganized attachment adaptation struggle with emotional dysregulation, and they can move through life with too little control, especially when it comes to their emotions. It can be hard for them to manage their feelings, which leads to a lot of acting out. Disorganized attached people may dissociate a lot and nervous system may shut down into freeze response as a defense to a hostile perceived environment. The primary contributor to disorganized attachment—as first identified by Mary Ainsworth—is when parents are the source of fear, and the children's attachment system shut down. Main ingredients for an upbringing environment that may result in disorganized attachment adaptation:

Disclaimer: Attachment adaptations are not personality traits or clinical diagnoses. We can oscillate between different styles depending on the situation and the person we are interacting with in a given moment. Source: Book "The power of attachment" from Diane Poole Heller. |

AuthorHi there! Archives

January 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed